Det er sjovt, som tingene nogle gange kan udvikle sig. Som nogle af jer måske vil vide, linkede jeg til et gammelt interview med Nikolas Schreck, hvor Lovecraft pludselig blev nævnt som inspirationskilde. Det var interessant, men selve interviewet måske nok mindre flatterende for Schreck i dag. Det blev især tydeligt, da hans medierepræsentant kontaktede mig og forklarede, at hr. Schreck efterfølgende har lagt sin politiske, satanistiske baggrund bag sig og i 2003 vendt sig mod buddhismen.

Hun nævnte i forbifarten, at Schreck engang havde kaldt sig et barn af ”the Lovecraft generation”. Et begreb, jeg egentlig synes, er ganske spændende, og derfor spurgte jeg, om ikke Nikolas kunne tænke sig at uddybe dette lidt nærmere. Det kom der en særdeles interessant korrespondance ud af, som jeg er rigtig glad for at kunne bringe i dette indlæg. Schrecks karriere har nemlig ikke bare bragt ham i kontakt med en lang række store navne inden for horrorgenren, hans ungdomsoplevelser fra 70’erne med paperbacks og horror giver et tankevækkende tidsbillede. Og dertil kommer en række andre synspunkter, som de fleste af jer sikkert vil finde helt interessante, at stifte bekendtskab med.

Men måske skulle jeg først lige genfortælle, at Schreck op gennem 80’erne var en af frontfigurerne i det avantgardistiske musikkollektiv Radio Werewolf, der identificerede sig som satanister og noget, der i hvert fald for omverdenen fremstod som ganske højreradikale synspunkter. Som det fremgår nedenfor, har Schreck taget stærkt afstand til sit ungdommelige jeg, men ikke desto mindre er det nok som højtprofileret satanist, at Schreck er bedst kendt fra medierne.

I dag er Schreck forsanger i bandet Kingdom of Heaven, men hans interesser dækker mange emner og kunstneriske udtryk, hvor ikke mindst samarbejdet med Zeena Schreck – Anton laVeys datter – har været vigtigt. Ikke mindst fordi Nikolas og Zeena har fulgt samme vej fra sort magi til tantrisk buddhisme. Schrecks okkulte interesse har også resulteret i en række bøger, der kredser om okkultisme og satanisme. Noget, der uddybes neden for.

Baggrundstoffet, de slibrige historier og Nikolas’ aktiviteter i dag som underviser, kan I læse mere om andre steder på Nettet. Her skal vi i stedet en tur tilbage til 70’erne med Schreck og høre et barn af ”the Lovecraft Generation” fortælle. Og det er som sagt blevet til en både spændende og underholdende snak. God fornøjelse.

***

A lot of quite, shall we say colourful, material is floating around the Internet about you. Thus before we begin, you should perhaps in your own words give us a brief introduction to the path which has led to your current status as artist and teacher.

If “colourful” is Danish for “bullshit”, then yes, there’s plenty of that floating around the Misinformation Highway’s cesspool. Just today, I learned from a Canadian anti-Illuminati blog that the sonic magic class I recently taught in Berlin somehow proves that the CIA mind control program MK ULTRA covertly took over America! Luckily, more accurate data abounds in several recent comprehensive interviews archived on my website, YouTube channel and Facebook page. I’ve obliged many other interviewers with short introductions on how my initiatory journey led from paganism, Devil Worship, and ceremonial magic to my current practice and teaching of Tantric Buddhism. But I’ve concluded that it’s impossible and even irresponsible to try to briefly convey the reality of mysticism, magic and metaphysics to those who’ve never dedicated themselves to any daily spiritual practice nor undergone a mystical experience. As all ancient wisdom traditions insist, the mysteries of the sacred can’t be understood intellectually on a theoretical basis. Since your blog’s dedicated to horror literature, this communication challenge is even trickier.

Many of your readers’ only exposure to the spiritual world may come through pop culture treatment of the supernatural, which provides a grossly distorted idea of the real thing. It suffices to say here that the gods and demons of various pantheons played a decisive role in my life since childhood, and that under the influence of the 1960s black magical revival, including the surge of interest in Satanic sorcery the horror boom of that period ignited, I dedicated myself to decades of ceremonial magic practice before abandoning Western occultism, first for the Hindu-based Tantric Vama Marga, before formally converting to Tantric Buddhism.

Given that the horror genre’s stock in trade is magic, demons, the survival of ancient gods, spells, curses, possession, life after death and reincarnation – the core themes of my everyday existence – I’ve always found it a paradox that so many horror authors and their readers are atheist materialists for whom these timeless phenomena are merely antiquated superstitions suited for escapist entertainment. Conversely, many gullible occultists wrongly believe that such genre figures as Lovecraft and his ilk revealed genuine initiatory wisdom in their fiction. Because I’ve dwelt in both worlds, perhaps I can help bridge this gap.

Your idea of a Lovecraft generation is intriguing. The wordplay is clever but should – I guess – not be taken literal. Nevertheless I like the concept as a way to grasp the almost explosive popularity Lovecraft and his wider circle experienced during the 1960s. Could you say a bit more about this?

I coined the phrase “Lovecraft Generation” in my 1994 Vincent Price obituary published in Lovecraft correspondent Forrest J Ackerman’s Famous Monsters magazine, which, during its 1960s heyday, was Holy Scripture for a mutant species of baby boomer so obsessed with the supernatural that it took on the religious dimensions of a genuine cult, the shadow side of the sunny good vibes of the hippies. It seemed a convenient label for the much darker nameless American subculture weaned on occult themes in horror and the renaissance of ceremonial black magic which that incomparably odd era spawned.

As you point out, this 60s go go ghoul craze was sparked by archaic creations from thirty years earlier, such as the televised revival of the old Universal monster movies and the mass paperback reprinting of the then-obscure work of such Weird Tales pulp fictioneers as Lovecraft and his circle. In a time when other fads were all about the latest youth culture novelty, this subculture looked back to the ancient past, which appealed to my love of the archaic. In that subversive anti-establishment “Sympathy for the Devil” Zeitgeist, however, the forces of darkness were no longer perceived as villains as they were in the 30s but were exalted by the young as anti-heroes worthy of emulation. Because the Lovecraftian opus’s re-emergence dovetailed with the rise of LSD-laced Luciferianism and the neo-witchcraft fad, poor Howard, rationalist atheist and fussy old maid prude that he was, must have spun in his unquiet Providence grave to see his tales inspire drugged Dionysian dropouts to embrace the kind of unspeakable magical rites that so repulsed him. In those days, the public didn’t know much more about Lovecraft other than his timely evocative name and his reputation as an eccentric recluse.

So the counterculture’s mystical wing could erroneously imagine him as a kindred spirit who shared their cosmic yearnings. I made the same mistake. Just as Hermann Hesse’s novels found a new readership among the spiritual seekers of the 60s, the proto-psychedelic aspects of Lovecraft’s work perfectly suited a time when acid routinely opened the minds of millions to exactly the kind of otherworldly landscapes and entities Lovecraft transcribed from his dreams.

As part of the “Lovecraft generation” could you tell us a bit about your first encounters with H. P. Lovecrafts fiction?

The way Lovecraft’s trans-Plutonian signal entered my radar in 1967 is telling of the times. I was captivated as a child by hearing the psychedelic band H.P. Lovecraft’s haunting “The White Ship” on the radio, a prime example of how the Flower Children adopted Lovecraft as a freaky forefather. So I first assumed “H.P. Lovecraft” was a typically whimsical Sgt. Pepperesque band name of the period, not a real person. I didn’t catch the Lovecraft bug until 1970, when I saw The Dunwich Horror in a seedy Boston movie theater, which helped crystallize my unwholesome obsession with diabolism in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, Altamont and the Manson murders. Laughably dated today, The Dunwich Horror seemed credibly contemporary then, updated to that psychedelically Satanic era, with Dean Stockwell as the obviously Mansonesque wild-eyed with-it warlock Wilbur Whately. What really grabbed me about the film was Les Baxter’s pioneering use of synthesizers in the atmospheric soundtrack, which spurred my burgeoning interest in dissonant electronica while forever branding itself on my mind as the quintessential Lovecraftian sound.

Equally stirring was Sandra Dee, Gidget herself, writhing orgasmically on an altar as her pelvis served as The Necronomicon’s book holder. Of course, Sandra’s bravura performance gave me a totally wrong idea of Lovecraft’s work! So when I sought out a collection of his stories hoping for more softcore sorcery, I was thoroughly disappointed by the deficit of female characters or any hint of the erotic in Lovecraft’s asexual universe of hysterical bachelors on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The sinister femme fatales lovingly limned in Poe, Stoker, Le Fanu and the erotic tension driving the gothic classics enthralled me, so their lack in loveless Lovecraft was a major let down.

Some of his ideas inflamed my imagination, even as I struggled with his poor execution. Still, for subjective reasons having less to do with his actual texts than the supremely strange times and suitable setting in which I read them, I underwent a brief but intense Summer of Lovecraft in 1970. I voraciously studied his stories for ritual procedure tips while living in a ridiculously appropriate small coastal Massachussets town of West Dennis, the perfect Lovecraftian locale. This quaint former whaling village neighbored Yarmouth, enough like Innsmouth to allow my vivid eight-year-old imagination to hope that any odd sound coming from Nantucket Bay late at night was Cthulhu rising.

Any story which has a particular significance to you?

“Dreams in the Witch-House” comes to mind. It’s one of Lovecraft’s most thinly characterized, adjective-laden and slapdash efforts, but the title intrigued me because my favorite haunt in nearby Salem was the Witch House, a 17th century site connected to the witch trials, which fascinated me as I ghoulishly followed every gory detail of the lurid occult-tinged coverage of the trial of Charlie Manson’s supposed “witches” on TV and in magazines. I was struck by the similarity between Manson’s name and that story’s imprisoned witch Keziah Mason, who, like Manson’s supposed coven, also left mysterious witchy symbols “smeared on the … walls with some red, sticky fluid.” When “Dreams in the Witch-House” first appeared in a 1933 issue of Weird Tales, it probably seemed absurdly unrealistic. But by 1970 you only had to open the newspapers to believe that murderous mystical cults sacrificing to forgotten gods might really be lurking next door.

My interest in ancient Egyptian gods and medieval Devil-lore’s “Black Man” also drew me to that story’s apocalyptic herald Nyarlathotep, the subject of a majestic sonnet of the same name in my treasured Ballantine paperback edition of Fungi from Yuggoth, a collection of Lovecraft’s poetry which I still find far more effective than many of his stories. When I learned that Lovecraft was basically a bookworm who barely experienced any meaningful contact with humans other than by correspondence, I understood why the most fully developed character he ever created was a book, namely, The Necronomicon.

Could you share some of your memories about being interested in genre literature during this golden age of pulp revival. I can imagine how exciting it must have been to go paperback hunting during the late 60’s and 70’s with all the old pulp material being collected in books and so much new stuff seeing the light of day at the same time.

Yes, it was an incomparably exciting time to be a connoisseur of the genre. But I only grasped its uniqueness in retrospect, since from about 1964 until it fizzled out in approximately 1974, it was so omnipresent as to seem normal. There was something uncanny in the air you had to be there to experience, but which left a tantalizing trace of its otherworldly aura behind in that age’s artifacts. One vivid memory is how merely browsing any ordinary newsstand’s paperback racks in those years could transport my imagination to other worlds as I stared in wonder at the bewitching array of gaudily colored demons, seductive vampiresses, sorcerers, moldering ghouls and other fiends beckoning from the covers of what seemed like more quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore than I could hope to read in one lifetime.

my imagination to other worlds as I stared in wonder at the bewitching array of gaudily colored demons, seductive vampiresses, sorcerers, moldering ghouls and other fiends beckoning from the covers of what seemed like more quaint and curious volumes of forgotten lore than I could hope to read in one lifetime.

The sheer visual intensity overload during that golden age of genre paperback cover art was as amazing as discovering the tales told between the covers. Some of my favorite books (and covers) from that period were edited by the British anthologist Peter Haining, who specialized in compiling obscure black magical and occult-themed fiction, treasure troves of infernal inspiration.

No “paperback hunting” was needed, because such spectacular strangeness was everywhere, and not only in paperback racks. I could read from this macabre cornucopia while taking a Creature of the Black Lagoon bubble bath thanks to Colgate-Palmolive’s Soakies, keep my allowance in a Wolfman wallet, fly a Count Dracula kite, listen to a plethora of ghoulish novelty tunes on the transistor radio through a speaker shaped like the Frankenstein’s Monster’s head, and as the decade darkened, rush home after school to turn the TV on at exactly 4 pm to watch “Dark Shadows”, required religious programming for all budding demon summoners.

Since the only films I was interested in were mostly banished to the post-witching hours, I’d force myself to stay up until 3 in the morning to watch, in a state of semi-comatose trance, some creaky old Creature Feature whose plot I already knew from articles in Famous Monsters or Castle of Frankenstein magazines, only to spend the weekend catching the opening of the latest Hammer, American International, or Amicus masterpiece, usually at the sleaziest movie theater in town. In short, like many others similarly afflicted back then, I could easily misspend my youth immersed in the ever expanding supernatural pop cultural explosion.

Though I enjoyed these extra-literary adaptations, I always judged them with fanatical zealotry based on their faithfulness to the original novels and stories they were usually loosely based on. Digging deeper to the source by studying the flood of reprinted demonology texts also reprinted at that time, my fundamentalist fury was roused by how casually authors and filmmakers ignored the ancient rules of genuine vampire, werewolf and demon lore.

What about the other authors from the so-called Lovecraft circle? Did they have an equal impact on you? For instance the works of Robert E. Howard whose popularity exploded in ways similar to Lovecraft’s

The whole Weird Tales package impacted me profoundly, from Margaret Brundage’s spicy Sapphic art on the cover to the very last page. Sure, he was a penny a word hack, but I admired the brutal panache of Robert E. Howard’s sweeping sword and sorcery sagas, more full-blooded and vivid than Lovecraft’s work, populated as they were by savage barbarian queens, she-pirates and semi-supernatural Stygian sirens, such as Thalis, “…tall, lithe, shaped like a goddess; clad in a narrow girdle crusted with jewels. A burnished mass of night-black hair set off the whiteness of her ivory body. Her dark eyes, shaded by long dusky lashes, were deep with sensuous mystery…” REH’s conviction that barbarism is preferable to civilization’s soft constraints appealed to me as a welcome alternative to the insipid “peace and love” bandied about in the Aquarian Age I was raised in, as did his Spenglerian vision of cultures in inevitable decay. Significant to my later spiritual development, my first awareness of the god Seth came not through Egyptian myth but through Robert E. Howard’s distorted depiction of Him as the Stygian theocracy’s supreme deity in the Conan tales.

Another Weird Tales alumni and Lovecraft correspondent whose way with the sinister feminine intrigued me was the unjustly forgotten Fritz Leiber, Jr.. Long before I fully understood what the left-hand path meant, this line from Leiber’s The Unholy Grail called to me: “You are more tempted by the hot lips of black magic than the chaste slim fingers of white, no matter to how pretty a misling the latter belong – no, do not deny it! You are more drawn to the beguiling sinuosities of the left-hand path than the straight steep road of the right.” Clark Ashton Smith’s insanely overripe ornately stylized prose intoxicated me, especially the erotic exoticism of the collection published in 1970 as Zothique.

I wanted to live in the chamber he described as “a room with tapestries of shameless design, where, on a couch of fire-bright crimson, the Princess Ulua sat with her latest lovers amid the fuming of golden thuribles” just as I longed to meet his “White Sybil” whose “tones filled him with an ecstasy near to pain. He sat beside her on the faery bank, and she told him many things: divine, stupendous, perilous things; dire as the secret of life; sweet as the lore of oblivion; strange and immemorable as the lost knowledge of sleep. But she did not tell him her name, nor the secret of her essence; and still he knew not if she were ghost or woman, goddess or spirit.” Smith’s self-described goal of crafting “verbal black magic” that worked “like an incantation” on the reader greatly influenced my own magical approach to the arts.

Frank Belknap Long produced only one minor masterpiece, “The Hounds of Tindalos” but it stuck with me as an original, convincing depiction of ritual evocation. Reading it in that druggie decade I thought that Long’s device of a fictional psychedelic substance was forward-looking for 1929. But I’ve probably found more consistent pleasure over the years in the varied works of Lovecraft’s underrated disciple Robert Bloch than in the rarefied realms of his more celebrated peers. Though he was a skilled craftsman rather than a visionary, Bloch demonstrated diversity and range, brought some welcome wicked black humor to the standard repertoire, and pushed genre boundaries, innovating in a career spanning the pulps of the 30s and 40s to adapting some of his tales into some of my favorite macabre films and TV shows of the 60s and 70s.

Were you also part of the Dungeons & Dragons boom in the 1970’s?

Many false accusations have been lobbed at me over the years, but that’s the most slanderous one yet! No, I never had the slightest interest in D&D.

I’m quite fascinated by the way the fiction of Lovecraft and to some extent also the works of Clark Ashton Smith has crept into occultism and Satanism. I could well imagine that you have some firsthand experience with this. Can you tell us a bit about this and also, what you have called “the unintentional negative impact Lovecraft, the Cthulhu Mythos and some of his peers have had on modern occultism and Satanism, misleading many into delusive fantasy realms”

Alex Berzin, a gifted Western teacher of Tantric Buddhism, once gave a lecture on this sort of thing, entitled “What Is the Difference between Visualizing Ourselves as a Buddhist Deity and a Deluded Person Imagining They are Mickey Mouse?”. Anyone practicing magic based on Lovecraft’s characters is doing Mickey Mouse magic. Lovecraft made his stance crystal clear when he wrote, “I am, indeed, an absolute materialist so far as actual belief goes; with not a shred of credence in any form of supernaturalism – religion, spiritualism, transcendentalism, metempsychosis, or immortality”.

And yet, it’s become an article of faith among occultists that Lovecraft was an unknowing prophet whose stories reveal cosmic Thelemic truths or Hidden Satanic Laws, a fallacy reaching its nadir in the mindless credulity of the Internet’s postmodern playground. Some Satanists see Lovecraft as a closet Luciferian, but consider what he wrote to Clark Ashton Smith: “The idea that black magic exists in secret today, or that hellish antique rites still exist in obscurity, is one that I have used and shall use again. When you see my new tale “The Horror at Red Hook”, you will see what use I make of the idea in connexion with the gangs of young loafers & herds of evil-looking foreigners that one sees everywhere in New York.” Does that provincial xenophobic disgust sound like it came from someone with the least sympathy for the Devil?

I first met seemingly intelligent people who believed that the Cthulhu Mythos was objectively real in London in the early 80s when I was involved with followers of Kenneth Grant, the first major occult figure to postulate as long ago as the 50s that Lovecraft was unconsciously a hidden Adept. From Grant’s Typhonian OTO, the notion spread to the then-new magical fad called Chaos Magick, and is still parroted among many occult factions today. Because I was so steeped in Weird Tales, when I first interviewed my future father in law Anton LaVey for a book I was writing in 1988, I immediately noted how much of his Church of Satan originated in Weird Tales stories LaVey read in his youth.

The Church of Satan newletter’s name comes from a fictional Satanic publication called “The Cloven Hoof” in a Robert E Howard story. LaVey made the trapezoid a key ingredient in his creed, but never mentioned its source, the Shining Trapezohedron from Lovecraft’s “Haunter in the Dark”. He claimed that “Die Elektrischen Vorspiele” in his Satanic Rituals was an authentic ceremony dating from the Weimar Republic, but much of it is stolen directly, and uncredited, from Frank Belknap Long’s “Hounds of Tindalos”. Long was appalled by its misuse when he learned of it from one of LaVey’s most avid followers. Zeena told me about a Church of Satan psychodrama she participated in as a child which her father based entirely on Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Weird of Avoosal Wuthoqquan”.

When I say it’s utterly futile and harmful to work magically with Lovecraftiana, I know my warning seems meaningless to those who believe the modern existentialist dogma that all gods were created by man, and thus consider Cthulhu no more fictional than any deity. But a core practice of ceremonial magic going back to ancient theurgy is to establish the bona fides of the spirits summoned so that the magician is not led astray by malicious imposters. Difficult enough when attempting to contact a spiritual being whose existence has manifested for many thousands of years, let’s say, Venus, Quetzalcoatl or Odin. Attempting to communicate with a character who we know is fictional, whether it be Chthulhu, Tarzan, Holden Caulfield, or Sabrina the Teenage Witch, is, at the very least, a complete waste of time, and at the worst, a symptom of mental illness. It shows a complete misunderstanding of the purpose of spiritual endeavor, and has no more meaning than Cosplay or other role-playing games.

Invoke Cthulhu, and all you’re likely to stir up is what remains of the mental residue of the depressed neurotic nihilistic human being who created it. That’s not to say that there isn’t a kind of magic in how writers conjure their characters to credible life in their minds and then to the minds of their readers, but that’s a whole other line of inquiry.

I know that you at one point were influenced, philosophically, by the writings of Lovecraft, but have you at some stage also sought religious truth in his fiction or for instance the fiction of Crowley?

No. The apocalyptic anti-human tenor of Lovecraft’s fiction left its traces in some of my earliest work, and I referenced his story “The Music of Erich Zann” in some of the first Radio Werewolf material, since it suited the theme of musical frequencies from other worlds. But I never agreed with Lovecraft’s atheist materialist scienticism. I included a sample of Aleister Crowley’s fiction for historical purposes in my 2001 anthology Flowers from Hell: A Satanic Reader, but the Great Beast’s cumbersome attempts at literature, along with his childishly inept paintings, reveal that he didn’t possess the truly creative artist’s mind necessary to being a competent magician.

Even at the height of my supremely selfish Satanic phase, Crowley’s personality, especially his cruelty to animals, repulsed me on a deep visceral level. Crowley was a pompous woman-hating toxic narcissist whose undeserved reputation, bolstered primarily by the Beatles, Jimmy Page, and Ozzy Osbourne, still leads gullible spiritual searchers to accept his woefully inaccurate misinterpretations of ancient tradition, thus leading them into a dead end. Magic is a universal natural activity of the human species, interwoven with the prehistoric roots of art, music, medicine, culture and governance. “Magick” as extolled by Crowley was an attempt to “brand” it with a Crowleyan trademark, just as his disciple L Ron Hubbard did more successfully by rebranding it as “Scientology”.

Crowley is the essence of what Rene Guenon described as “counter-initiation”, a false path whose allure distracts one from true spiritual wisdom. Crowley’s creed of finding and acting on one’s “True Will” is a self-destructive exaltation of a permanent Self, or ego, which is the root cause of all suffering. Zeena and I comprehensively critique Crowley in our book Demons of the Flesh, so I won’t be too redundant here.

As professionally a researcher on rituals I find the transformation from fiction into religious practices immensely fascinating. At least to my mind it fundamentally seems to shed some light on the way we continuously construct and elaborate metaphysical ideas to accommodate our current situation. While Lovecraft et al aren’t the sole example of this they certainly seem to have had a particularly strong appeal. Why do you think that is?

For the same reason starving people gorge themselves on the empty calories of fast food if that’s all that’s available. Since the West severed its connection to the ancient myths and sacred lore which once nourished us, our long lost gods have been replaced by the ersatz quasi-religion provided by such newly fabricated pop culture myths as Lord of the Rings, The Cthulhu Mythos, the Star Wars franchise, all of which I’ve seen adopted as spiritual prototypes by many deluded occultists. This went on long before Lovecraft, the most striking example being the pious Christian John Milton’s Paradise Lost unintentionally inspiring 19th century Satanists to revere the Fallen Angel, as William Blake famously observed in his statement, “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it“.

Another author of fiction assumed by such notoriously unreliable 19th century occultists as Rudolf Steiner and Madame Blavatsky to reveal initiatory truths was Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, whose unreadably bad novels Zanoni and The Coming Race influenced Theosophy and the Golden Dawn, giving birth to the notion of “Vril” a completely fictional idea which many misguided occultists and conspiracy theorists still believe is a genuine historically attested spiritual phenomenon.

A very useful angle from which to regard this phenomenon is L Ron Hubbard, a 1930s pulp fiction fantasist who dabbled in Crowleyan magic deliberately creating a false neo-religion as a money-making scheme, whereas in Lovecraft we have a 1930s pulp fiction fantasist’s stories adopted posthumously by his mentally unhinged fans and transformed into a false neo-religion. Hubbard’s Xenu and Lovecraft’s Cthulhu are more closely related than it seems. My late friend Forry Ackerman, who dealt with both Lovecraft and Hubbard, working as the latter’s literary agent, told me many anecdotes of how Hubbard, in the late 30s, before he dreamed up Dianetics, dropped mysterious hints about his writing a secret book of esoteric wisdom called Excalibur, which would supposedly drive anyone who read it mad. Of course, nobody ever saw this non-existent fabled manuscript. I think it’s very likely that Hubbard based this gimmick, the seed of Scientology, on reading about his pulp peer Lovecraft’s The Necronomicon.

Ultimately, I think the answer to your question lays in the fact that genuine initiation in any real spiritual tradition rooted in ritual requires intellectual rigor, discrimination, and disciplined training of your own mind, whereas its much easier and more fun to scratch a casual spiritual itch by simply reading a dualistic fictional narrative without any of the hard work true spiritual practice demands. It’s also worth examining this groundbreaking recent research, brought to my attention by Zeena, suggesting that despite his skepticism about the supernatural, Lovecraft almost certainly plagiarized essential aspects of his Mythos from the occult writings of the Theosophist Alice Bailey.

Do you for instance think that novels like The Devil Rides Out and Rosemary’s Baby, which both culled occult trivia, also had an impact on the development of modern Satanism?

Absolutely. The basic contention of my book The Satanic Screen and its companion volume Flowers from Hell is that almost all of what the general public knows as modern Satanism is an artificial patchwork quilt sewn together from bits and pieces of classical literature, especially Dante’s Inferno, Goethe’s Faust and Milton’s Paradise Lost, and its later debased popular derivations in Wheatley, Ira Levin and others, finally crystallizing in mass consciousness in cinematic portrayals of diabolism. I would go so far as to argue that there would be no modern Satanism as we know it were it not for Wheatley’s influence on British occultists since the 1930s and the even wider worldwide sociocultural impact the popularity of the novel and film Rosemary’s Baby exercised on the imagination of a generation peculiarly receptive to a shift in perception about the Devil.

Of course, it’s a chicken and the egg quandary, as it makes perfect sense that the Devil would seek to enter the minds of millions through apparently harmless popular entertainment crafted by such atheist non-believers as Ira Levin and Roman Polanski. So there is a serious spiritual riddle looming behind those events, namely the enduring mystery of what metaphysical doorway opened between the worlds in the 1960s before slamming shut in the mid-70s.

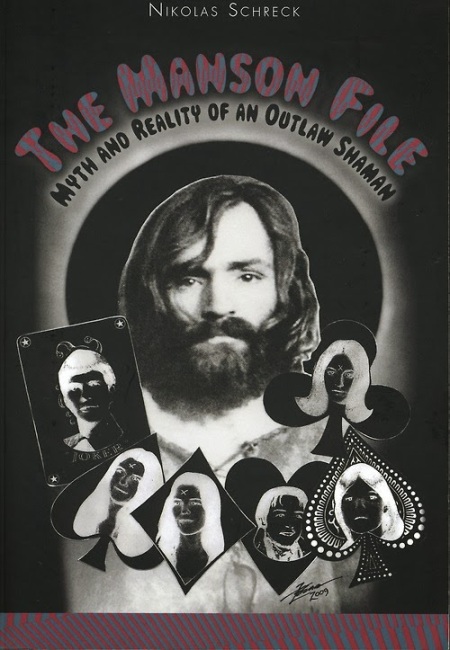

You are the author behind several publications. The Manson File (1988) for instance. But also Demons of the Flesh: The Complete Guide to Left Hand Path Sex Magic from 2002 and The Satanic Screen: An Illustrated Guide to the Devil in Cinema. Quite diverse topics! Can you tell us a bit more about these books?

All of my books to date draw on my own personal experience to fill gaps in knowledge about arcane subjects which everyone thinks they understand, but actually don’t. My underlying unifying theme, despite the diversity of topics, is exploring the difference between conventionally perceived consensus reality and the way things actually are. My recent greatly expanded second edition of The Manson File: Myth and Reality of an Outlaw Shaman examines in depth the complex facts beyond simple popular fantasies concerning Charles Manson’s philosophy, spirituality, music, life and crimes, revealing that the so-called “Manson murders” were not random ritual killings intended to start “Helter Skelter”, but were simply a series of botched drug deals between criminal associates whose Mafia connections were covered up to protect the careers and reputations of the many movie and rock music celebrities involved.

Demons of the Flesh: The Complete Guide to Left Hand Path Sex Magic was a collaboration with Zeena which set out to foster understanding from the perspective of practitioners on the vastly misunderstood topic of “the left hand path”, a phrase hijacked and hopelessly misunderstood by Western occultists but which is actually a yogic tradition rooted in Eastern Tantra devoted to worship of the feminine principle. The Satanic Screen was the first book to document the history of the portrayal of the Devil and Satanism in the cinema, delving into the synergy of how genuine occult practice influenced these films, just as the films went on to influence genuine occult practices.

Do you still read horror literature?

I occasionally dip into worthy entries from earlier eras, and am glad to stumble onto an unknown or forgotten gem, but for the most part, I stopped keeping up with the genre in the mid-80s. One reason is that the deeper one delves into spiritual experience, the less convincing and inspiring even the most realistic fictional portrayal of the supernatural becomes. I started to lose interest when gothic supernaturalism rooted in European folklore gave way to crude depictions of physical violence for its own sake in the splatter/slasher subgenre.

My snobbish elitism was also offended by the increasingly plebeian Joe Six Pack effect of Stephen King, who sanitized what was once a sleazy and disreputable dark corner of literature for outsiders into a brightly lit McDonalds for the masses. The final nails in the coffin were driven in by Anne Rice, who defanged the creatures of the night, turning them into a politically correct misunderstood minority of fey dainty whiners, an unfortunate trend continued by the post-Hellraiser Clive Barker, and degenerating into the ghastly abomination that is Twilight and its many imitators.

During your long career you have been in contact with a host of quite prominent people – Robert Bloch, Vincent Price and Christopher Lee to name a few. How did you for instance get in contact with Bloch?

Yes, I’ve been privileged to get to know and to work with many genre icons whose work I’ve admired over the years, but since we’ve focused here on Weird Tales and its echoes, I’ll stick to Bloch. I first met him in 1976, when he, along with the surreal combination of Ray Bradbury, Groucho Marx, and Timothy Leary, was a guest at the Los Angeles Book Fair held in the long since destroyed Ambassador Hotel, the site of Robert Kennedy’s assassination. Despite his legendary reputation, he was completely approachable. Perhaps because his mentor Lovecraft had been so helpful to him in the 30s when Bloch was an aspiring teenage writer, he too was generous with his time to me and to many other would-be writers.

I think he was sick of being remembered only for Psycho so he was probably relieved to hear someone so young enthuse about some of his more obscure tales, such as the pleasingly perverse “A Toy for Juliette”, “The Past Master”, “The Cloak”, “The Living Dead”, “Return to the Sabbat”, “The Skull of the Marquis de Sade” and his Amicus film anthologies. After graciously looking over some of my short stories which I’m sure were awful, he later gave me several eminently practical writing tips. In private, his gallows humor was sharper and more profane than in his books, and his no-nonsense approach to writing as professional craft and daily discipline was a useful antidote to any romantic adolescent notions about waiting for the Muse I may have otherwise entertained. Bloch was adamantly uninterested in occultism, but was at least open-minded and more amused than alarmed by my open pursuit of magic, which hasn’t always been the case with other genre figures I’ve known. I often saw him as a speaker at meetings of the Count Dracula Society run by Dr. Donald Reed, a classic grotesque Day of the Locusts Hollywood character of the old school.

The Count Dracula Society was the last remnant of a Los Angeles tradition of magicians mingling with authors of fantastic fiction that went back to the days when Jack Parsons and other occultists hung around with Heinlein and Bradbury at the old Clifton’s Cafeteria meetings of The Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society in the late 30s. I kept in touch with Bloch until 1983 when I drifted away from that fading milieu, but honored him by quoting his line “a clown after midnight isn’t funny” in the Radio Werewolf song “Pogo the Clown” a very Blochian character study of a serial killer.

And here we arrive at the end of the correspondence. Thanks for the Interview Nikolas and good luck with your future endeavors.